|

|

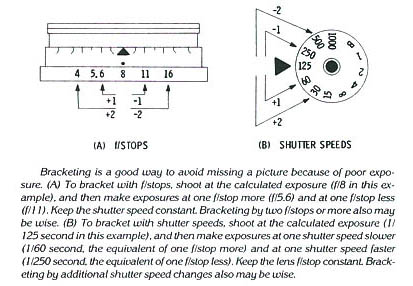

Determining Exposure I’ve continually mentioned the need to use an exposure meter (whether built into the camera or a hand a held model) to obtain the proper exposure for your picture. There are exceptions, however. While an exposure meter is one of your most valuable tools for making effective photographs, exposure can be determined in other ways. Some photographers, caught without a meter take an experienced guess and then shoot at various exposures. This is called bracketing your exposure. To bracket, you make two or more exposures that are over and under the exposure you think is correct. For instance, if 1/125 second at f/8 is your estimate of the correct exposure, you also shoot frames at f/5.5 and f/11. This minimizes the chance of missing a picture because of improper exposure. Bracketing two stops each way is even better insurance. Then you would also make exposures at f/4 and f/16, as well as at f/8, f/5.6, and f/11. Bracketing also can be done by varying shutter speeds. Thus you could bracket an exposure of 1/125 second at f/8 by shooting two more frames at 1/60 and 1/250 second. To bracket with shutter speeds the equivalent of two f/stops each way, you would keep the lens opening at f/8 and make additional exposures at 1/30 and 1/500 second, as well as at 1/125, 1/200, and1/250 second. Bracketing at half-stops is sometimes advised since it has less latitude for exposure mistakes. As a rule, however, you should use only the lens aperture to achieve bracketing at half-stops; setting the shutter speed dial between marked shutter positions may cause mechanical damage to your shutter, unless it is electronically controlled. Check your camera manual for additional advice.

What is the correct exposure? Quite simply, it is the f/stop and shutter speed combination that gives the photographer the result he wants. An exposure meter which is much more accurate than the photographer’s educated guess is still only a tool. The final photographic result depends on how the photographer uses the meter and Setting the ISO/ASA speed on the meter indicates to the meter how sensitive to light, and the meter calibrates exposure settings accordingly. To put it another way, the exposure meter does not know the speed you set your camera, so you must tell the meter by setting the proper ISO/ASA. Failure to adjust the meter for the correct ISO/ASA will result in improper exposure calculations. Caution: Some exposure meter ISO/ASA dials easily slip or can be knocked off the correct setting. Tape the dial in position, if necessary. The space available to list various ISO/ASA numbers on exposure meters is sometimes limited, especially with the ISO/ASA dials used on cameras with built-in meters. Often just a few ISO/ASA numbers are listed, with dots or lines to indicate the rest. Exposure Meter FactsExposure meters are generally of three types: 1) meters that are separate from the camera, called hand-held meters; 2) meters that are built into the camera and indicate the correct exposure when the photographer manually turns the f/stop and shutter speed controls; and 3) automatic or electric eye (EE) meters in the camera that electronically set the shutter speed or f/stop, or both. In all cases, the meters must read and react to the light present. The earlier types of light meters were limited to hand-held types. They had a long lasting light sensitive selenium cell that required no batteries. Light striking the cell would cause a current that moved the meter's needle to indicate exposure possibilities on an adjustable scale. These selenium cells were also used in the first electric eye automatic cameras in 1938 by Kodak and later in 1956 by Agfa. Hand-held selenium cell exposure meters are still manufactured but are considered by many photographers to be obsolete. That’s because progress in electronics and chemistry yielded a battery operated cadmium sulfide (CdS) cell, and it was incorporated in cameras as part of built in exposure meters. In fact, CdS type meters built in the camera were the most common light-reading devices until newer exposure reading cells, like the silicon photo diode (SPD) and gallium photo diode (GPD), began to replace them in 1978. The SPD, GPD, and CdS cells have been further utilized to control shutter speeds and f/stops, and thus they have become key elements in cameras with automatic exposure control. One or two small silver oxide or mercury batteries or a larger lithium battery, ranging from 1.5 to 6 volts, powers the exposure metering cells. The battery life in such models usually depends on the number of times the flash goes off. Most cameras have a method for checking the batteries so you can see if they are strong enough to give accurate readings and/or operate automatic exposure controls. The mercury batteries for exposure readings are supposed to last at least one year. However, many photographers make it a habit to replace these relatively inexpensive batteries at least once a year. The battery’s location will be indicated in your camera manual. lf your meter or automatic exposure controls cease to operate, a worn-out battery usually is the problem. Most cameras have an on-off switch for the metering system, and if left on for an extended period, battery drain can be excessive. This especially is a problem for models in which the batteries also power light-emitting diodes (LEDs) in the viewfinder to indicate exposure settings. Cameras with automatic exposure control can cause considerable battery drain, too. Smart photographers carry spare batteries, especially if they have important pictures to make and don’t want to chance sudden meter failure or in operation of automatic exposure controls. The batteries are available in nearly every camera store, even overseas. If your meter fails, and the battery is still fresh, check the metal contacts. A thin chemical film often develops on the battery's surfaces and breaks the electrical circuit. You may not see evidence of battery leakage or corrosion, but the whitish chemical coating which develops on the battery is enough to cause your meter to operate erratically or not at all. Wipe the battery and contacts with a clean handkerchief, not your fingers. Replace it properly according to polarity markings ( + and - )and then check the meter. If it still doesn't work, a faulty switch or a break in the internal electrical circuit is probably the trouble. You'll need a camera repair service. Never disassemble a meter yourself unless you never want to use it again. One thing to remember about battery-operated CdS cells is that they can suffer temporary fatigue under certain exposure conditions. The most common mistake is pointing the meter directly at the sun for an extended period of time; the bright light overwhelms the cell's circuitry and can result in faulty meter readings for minutes to hours afterward. It will recover, however. Here's how to check your CdS meter if you are going to make a reading directly toward the sun. First take a reading of a nearby subject in the normal manner. Remember the exposure setting. After taking your reading of the sun, and your pictures, take another reading of the same subject read earlier. If the meter results are the same, and lighting conditions have not changed, your meter is okay. If it gives a different reading from the first time, the sun has affected your meter. A CdS meter also may take a few seconds to adjust if you read a bright scene and then take a reading in the shade. Ultraviolet "black" light, such as the kind used for stage effects, will affect the CdS meter, too. Once affected by such light, recovery time may be a day or longer. The problem of CdS cell fatigue and less than instantaneous reaction to changes in light has prompted many manufacturers of cameras with automatic exposure control to use the newer photo diodes for measuring the light that passes through the lens. These silicon and gallium diodes provide faster and more accurate response to light, and they are considerably more sensitive than CdS cells when light levels are low. Photo diodes vary slightly in their characteristics and camera manufacturers favor different types. Since silicon photo diodes are sensitive to infrared rays, they are fitted with a filter to prevent the infrared from causing improper exposures. Silicon blue diodes incorporate this filtration and are said to give more accurate readings in all kinds of light. Another type, silicum, is said to give an even more reliable response to the different colors in the spectrum. Users of gallium photo diodes, sometimes described as gallium arsenide phosphide photo diodes, claim that the GPDs are completely insensitive to infrared rays, and that they are more accurate in low light levels and are less affected by hot or cold temperature extremes than the silicon cells. From a practical standpoint, the minute differences in diodes will not be evident in the exposure readings they give, but remember that the gallium and silicon diodes have significant advantages over CdS cells because they react more quickly to changes in light and are more sensitive in low levels of light. Since selenium meters require no batteries, some photographers feel more assured using this type of hand-held meter to make exposure readings. A booster an additional light-sensitive screen, usually can be attached when the light level is low. Other selenium meters have built-in high and low adjustments to set for bright or dim lighting conditions. However, GPD, SPD, and even CdS meters are better than selenium cell meters for making accurate readings in low light situations. Most hand-held meters can be readjusted if the needle which indicates the light reading gets out of register; A screw is turned until the needle remains on the zero position when no light is reaching the cell. When making this zero adjustment, cover the cell opening completely. With battery-operated meters, remove the battery. If you are careful not to drop or abuse the hand-held meter, such realignment is rarely necessary. Keep any meter on a strap around your neck. But don’t let the meter bang against your body or camera equipment. And keep the meter's case on when it is not being used. Zero correction is not possible with built-in meters, except by a repairman. Some hand-held meters indicate exposure with digital readouts using liquid-crystal display (LCD) or LEDs instead of a needle indicator, and most can be recalibrated by the photographer for accurate light readings without going to a repairman. Regardless of the type, exposure meters have proven to be the most popular and accurate devices for determining exposure. The major limitation of any meter is really

the person operating it. lf you don’t know how to make meter |

|

Even with the use of an exposure meter, bracketing is often done by professional photographers to ensure getting the correct exposure. It may seem expensive to make two or four more exposures of the same subject, but it may mean the difference between getting or missing a great picture.

Even with the use of an exposure meter, bracketing is often done by professional photographers to ensure getting the correct exposure. It may seem expensive to make two or four more exposures of the same subject, but it may mean the difference between getting or missing a great picture.